La corrente del golfo potrebbe cessare

THIS is a tale of two towns; both modest, yet possessed of a certain civic pride; both nestled at the edge of the ocean, sharing almost exactly the same latitude. In Churchill, Manitoba, in northern Canada, the winter is long. The snow is deep, the sea freezes far and wide as the thermometer falls to minus 50C. There are only two months a year without snow. When the polar bears emerge from hibernation, they gnaw the dustbins in search of scraps. Churchill, in short, is not a place to grow wheat and roses, potatoes and apples. There are no green dairy farms on the tundra shores of the Hudson Bay.

In Inverness, on the east coast of Scotland, the winters are very much gentler and shorter. Cold, yes, but not cold enough for skidoos, treble-glazed windows or snowshoes to school. The nearby Black Isle has some of Scotland's richest arable farmland. The enormous difference between the climates of these two towns is due to one thing: the Gulf Stream, which brings tropic-warmed sea from the Gulf of Mexico to the Atlantic coasts of northern Europe. Thanks to the Gulf Stream, on fine summer days people can swim in the sea from the pale golden beaches of the Lofoten Islands in Norway - 300 miles north of the Arctic Circle. In coastal gardens beside its warm waters, sub-tropical plants and exotic flowers flourish.

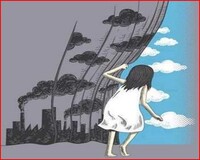

If there were no Gulf Stream, Britain would be as cold as Manitoba. We would probably be able to walk to Germany across the frozen North Sea. Our farmers would be defeated by permafrost but caribou would thrive on the lichens beneath the snow. Dairy herds would not wind o'er the lea nor honeysuckle twine about our cottage porches. The Gulf Stream has not always flowed. As far as scientists can tell, it has stopped quite abruptly in the past - and in as little as a couple of years. Now it seems that global warming is recreating the very same conditions which caused it to stall before, with the potential to plunge the whole of northern Europe into another Ice Age.

Which is a difficult concept to grasp as we slosh around in our sodden, rainswept towns and villages; as we discuss the extraordinarily late autumn and give up hoping for a white Christmas. Global warming was going to bring Mediterranean holiday weather to Brighton and vineyards to Argyll, wasn't it? Global warming is the reason why spring-flowering iris and cistus are blooming crazily in November. So how could it turn England's green and rather tepid land into a frozen waste? It is a question that will be exercising the minds of senior government ministers next week when The Netherlands hosts the sixth session of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Known as as COP6, this is the conference of the parties to the Kyoto protocols that were adopted in 1997 when the world's industrial nations reluctantly agreed to make some compromises in an effort to save the planet. They quarrelled and made deals and did a lot of special pleading and agreed on certain key things which would slow down climate change and reduce environmental depredation. Targets were fixed for restrictions on out-of-town developments which encourage the use of private cars; reduced reliance on fossil fuels and funding for alternatives; plus more use of energy-saving technologies. At The Hague next week ministers will have to come to grips with a bewildering array of scientific evidence - much of it conflicting - about what is happening to our climate.

A vital clue lies in the Arctic Circle, buried deep within the ice pack. International research teams have spent three decades drilling holes to extract ice cores from the Greenland ice pack which contains a tenth of the world's fresh water. Among the team members was Richard Alley, one of the world's leading climate researchers and professor of geosciences at Pennsylvania State University. His forthcoming book about their activities, The Two- Mile Time Machine, reveals what the ice cores have to teach us.Central Greenland is cold enough for snow to fall all year, but the summer sun "cooks" the snow so that annual layers, analogous to the growth rings in tree trunks, are clearly visible in the cores. In places the Greenland ice pack is two miles thick, so a core, a two-mile-long vertical cylinder drilled out of that ice, yields a detailed history of the earth's climate during the past 110,000 years.

Alley's first striking finding is that the earth's climate has always been wildly variable and subject to sudden and dramatic swings - except during the past 10,000 odd years. So the period during which humankind has established itself across the globe and made the transition from grubby bands of hunter-gatherers to the dubious majesty of global capitalism corresponds exactly to a freakishly stable period in the earth's climate. Not that the climate has remained unchanged within that period: there were the cold centuries which drove the Vikings off the colonial foothold they had established in Greenland, and the freeze-up in the 17th century when Londoners held winter revels on the frozen River Thames. But these are mere blips on the screen compared with the drama revealed by the ice cores.

At one time, for example, so much ice got stacked up at the poles that the sea levels went down 400 feet and the primeval rambler could have walked from Newcastle across a land bridge to Denmark. The most worrying of Alley's findings is that not only is the world's climate inherently unstable, but it also turns out that large changes in climate can be set off by quite small triggers.

For example, a relatively minor increase in temperatures in the Arctic has the potential to shut off the flow of the Gulf Stream, resulting in a dramatic change in Britain's weather. The Gulf Stream consists of warm, salty water which flows from the hot tropics north on the surface of the Atlantic to the Arctic. In the winter these ocean waters give up their heat to warm northern Europe and, when sufficiently cooled, sink to the ocean depths. They then flow back south along the ocean bed, out of the Atlantic, and eventually rise to return, years later, to repeat the whole operation. Since (you remember this from school) salty water is heavier than fresh water, it is rather important to our wellbeing that the water from the tropics is sufficiently saline. For if the incoming Gulf Stream water was too fresh, it would simply stay on the surface of the Arctic Ocean and freeze. If there were no water sinking, there would be nothing to draw the warm replacement water in from the south, and the whole process would simply stop.

Such an event would make the chaos of the last El Niño look merely trivial. And, according to some researchers, such a catastrophe could be imminent. The way for it to happen would be for the ice caps - which are composed of fresh water - to start melting in sufficient quantities to dilute the Gulf Stream and prevent it from sinking. According to America's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, it would take no more than a quarter of 1 per cent more fresh water flowing into the North Atlantic from melting glaciers to bring the northwards flow of the Gulf Stream to a halt.

In August this year, a tremor of apprehension ran through the scientific community when the Russian icebreaker Yamal, on a tourist cruise of the Arctic, muscled its way through unusually thin ice to the North Pole to find itself sailing serenely into an astonishingly clear blue sea. The tourists, who happened to include James McCarthy, an American oceanographer and one of the scientists working on the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), were the first human beings to see the sea at 90 degrees north. McCarthy described their reactions: "There was a sense of alarm. Global warming was real, and we were seeing its effects for the first time that far north."

THE LAST time a sudden influx of fresh water turned off the Gulf Stream was around 8,400 years ago, "A great flood through Hudson Bay after the collapse of the remnants of the Canadian ice sheet triggered a sudden cooling," says Alley. "Temperatures dropped about 6C for a century in Greenland, with cold, dry and windy conditions spreading across at least much of the northern hemisphere. "Perhaps the climate is easier to kick into a new mode of operation when carbon dioxide, sunshine or other important parts of the system are changing. The climate then might be a bit like a drunken human - when left alone, it sits, but when forced to move, it staggers."

This has serious implications for our future. Because no matter how many Earth Summits are held, and no matter how many promises and agreements are made, humans are highly likely to go on burning fossil fuels and inexorably warming the world by increasing the greenhouse gas concentration of the atmosphere. "We are pumping out carbon dioxide much more rapidly than nature did during the ice ages," warns Alley.

The 1990s were the warmest decade since records began and heat is a form of energy --- more energy equals more exciting weather. Floods, heatwaves, avalanches, blizzards, hurricanes, droughts - there seems to be more weather around now than any of us remember in the past. And there are more of us to bear the brunt of it. Hurricane Mitch was an ordinary bad storm which hit a particularly vulnerable place - and killed 9,200 people in Belize and Guatemala, in Central America. Countless people in Britain have been stranded and many more have been made temporarily homeless by the storms and floods of the past three weeks. The IPCC and the World Meteorological Organisation, consisting of more than 2,000 scientific and technical experts, is no longer equivocal about global warming. It states explicitly that it exists, that human activity is contributing to it and that its effects will be harsh.

Even serious vested interests are taking note. On October 18, for instance, seven multinational companies, including Shell, BP, Alcan and Du Pont, went into partnership to lobby for "market- based methods" to cut greenhouse emissions.

In Britain, Tony Blair has pledged an extra £100 million towards recycling schemes and the development of "green power" sources such as wind farms. But is this all too little, too late? "We have to face a stark fact," says Blair, "Neither we here in Britain, nor our partners abroad, have succeeded in reversing the overall destructive trend. "The truth is, these problems are more urgent and more pressing than they have ever been and the solutions at the moment do not measure up to the scale of the problem. It is a very big issue for us."

However, while Blair may express enthusiasm for reducing emissions from power stations, he seems less inclined to tackle the second biggest culprit in the production of greenhouse gases: the motor car. Politicians learnt from the recent worldwide fuel blockades that there are few votes in increasing fuel taxes. Perhaps it is time for individuals to take the initiative. We could begin by realising just how much carbon and carbon dioxide are added to the atmosphere every time we boil the kettle, drive to the supermarket or fly off to the sun.

The alternative? Well, it could just be polar bears stalking the Thames beside an iced-up Houses of Parliament - now emptied of those politicians who failed to grasp the nettle.

Articoli correlati

Le conclusioni del vertice mondiale sul clima

Le conclusioni del vertice mondiale sul climaCOP29: occorre ridurre le spese militari per la transizione ecologica

I 300 miliardi promessi sono una goccia nel mare rispetto ai 2.400 miliardi stimati come necessari per contenere il riscaldamento globale entro 1,5°C.24 novembre 2024 - Alessandro Marescotti Rapporto catastrofico dell'ONU sul clima

Rapporto catastrofico dell'ONU sul climaIl Pianeta sull'orlo del baratro

Il Segretario Generale dell'ONU, Antonio Guterres, ha lanciato un allarme per l'inquinamento da combustibili fossili. Il rapporto sottolinea che nel 2023 la temperatura media era di 1,45 gradi sopra i livelli preindustriali. Avvicina il pianeta alla soglia critica di 1,5 gradi, concordata nel 201519 marzo 2024 - Redazione PeaceLink L'accordo sul Global Combat Air Programme (Gcap) è stato firmato a Tokyo anche dal governo italiano

L'accordo sul Global Combat Air Programme (Gcap) è stato firmato a Tokyo anche dal governo italianoNuovo spreco di risorse nei caccia di sesta generazione

La sostituzione di 240 jet Eurofighter con il nuovo caccia rappresenta per noi pacifisti un impegno non condivisibile che sposta risorse dal campo civile a quello militare. La cooperazione internazionale per la lotta ai cambiamenti climatici e alla povertà estrema viene prima di ogni altra cosa.14 dicembre 2023 - Redazione PeaceLink Webinar su COP 28, militarizzazione e ambiente

Webinar su COP 28, militarizzazione e ambienteRidurre la spesa militare è fondamentale per contrastare i cambiamenti climatici

Co-organizzato da quattro prestigiose organizzazioni - l'International Peace Bureau, Global Women’s United Against NATO, No to War, No to NATO e l'Asia-Europe People’s Forum - questo webinar cerca di favorire una comprensione più profonda della complessa interazione tra militarizzazione e ambiente.10 dicembre 2023

Sociale.network